The Future of Earth: A Mirror of Mars’ and Venus’ Past?

For decades, the idea that Mars may have once hosted an advanced civilisation has been the subject of speculation, whispered in the corridors of both science fiction and scientific inquiry. The notion that an ancient Martian society, one much like our own, might have risen and fallen under the weight of its own technological advancements has intrigued many. Some theories even suggest that Mars’ inhabitants, faced with a dying world, may have sought refuge elsewhere—perhaps even on Earth. But rather than engaging in that argument, we consider a different angle: Could Earth, in a billion years, come to resemble the desolate, red expanse of Mars today?

Mars and Venus: The Planetary Lifecycle

The more we study Mars, the more evidence emerges that it was not always the dry, barren wasteland we see now. Scientists have found signs of ancient rivers, lakes, and perhaps even oceans. At some point, however, the planet lost its atmosphere, its water boiled into space, and all but the hardiest extremophiles perished—if life ever existed there at all.

Venus, on the other hand, presents a different cautionary tale. Once thought to be similar to Earth, Venus experienced a runaway greenhouse effect, leaving it a hellish world where surface temperatures exceed 460°C. Thick clouds of sulphuric acid now prevent infrared radiation from escaping, locking the planet in a feedback loop of ever-increasing heat. If Mars is an example of what happens when a planet loses its atmosphere, Venus is a case study in what happens when an atmosphere becomes a prison. Earth, positioned between these two extremes, is not immune to a similar fate.

Theory

If civilisation once existed on ancient Venus or Mars, perhaps it too relied on plastics, hydrocarbons, and industrial chemicals, poisoning itself in the same way we are doing on Earth. If Mars’ soil is, in part, the dust of its lost civilisation—ground down remnants of synthetic materials like plastics—then Earth would face the same fate. Whether this is likely true or not, the harsh reality is that fixing planet Earth could become so expensive and technologically challenging that leaving it might be seen as a more viable option. Even today, forever chemicals—those synthetic compounds that resist breaking down—have been found in some of the most remote places on Earth, including Antarctica. This suggests that no part of the planet is immune from industrial contamination, and the problem will only compound over time (CHEM Trust, 2024).

The Denial of an Unfolding Catastrophe

Despite overwhelming evidence, the response to environmental collapse is, at best, fragmented, at worst, deliberate obfuscation. Climate change, for instance, is often mischaracterised as simply ‘global warming’—a phrase that fails to capture the full battery of poisons and toxins being injected into the Earth’s atmosphere, soil, and even our own bodies. It is not just about temperature increases; it is about the wholesale transformation of the Earth’s biosphere. Just as opponents of evolution create strawman arguments that humans could not have evolved from apes—misrepresenting the actual scientific theory—so too has the debate on climate change been derailed by distractions, omissions, and deliberate misdirection. The real crisis is not only the warming climate but the inexorable accumulation of synthetic materials and hazardous compounds that will outlive humanity itself.

We are witnessing the slow-motion poisoning of an entire planet, yet policies continue to be driven by short-term economic interests rather than long-term planetary survival. This raises a troubling question: Is the world unwilling or simply incapable of action? If the latter, then the fate of Earth is already sealed, and, much like the imagined Mars past at the beginning of this artcile, we are merely living out the final centuries before planetary collapse.

The Plastic Paradox in Modern Manufacturing

In the era of Industry 4.0 and the forthcoming Industry 5.0, the integration of advanced technologies like automation, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things is transforming manufacturing processes. However, a critical paradox lies at the heart of this technological revolution: the pervasive reliance on plastics.

3D Printing and Plastic Dependency

Additive manufacturing, commonly known as 3D printing, is heralded as a cornerstone of modern manufacturing. It enables rapid prototyping, customisation, and complex designs that traditional methods cannot easily achieve. Yet, the majority of 3D printers utilise plastic-based materials, such as polylactic acid (PLA) and acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS). This dependence on plastics underscores a contradiction: while aiming for innovation and sustainability, the industry continues to rely on materials that contribute to long-term environmental degradation.

Plastics in Electric Vehicles

The automotive industry, particularly the electric vehicle (EV) sector, exemplifies this paradox. EVs are promoted as environmentally friendly alternatives to fossil fuel-powered cars. However, they incorporate significant amounts of plastic to reduce weight and improve efficiency. According to the American Chemistry Council, an average mid-size EV contains approximately 450 pounds (204 kilograms) of plastics and polymer composites—140 pounds more than a comparable internal combustion engine vehicle. This accounts for about 10% of the vehicle’s weight but nearly 50% of its volume (American Chemistry Council, 2023).

The Persistent Production of Hazardous Materials

Beyond plastics, the continued manufacture of ‘forever chemicals,’ such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), poses severe health risks. These chemicals are renowned for their persistence in the environment and human body, leading to potential adverse health effects. Despite growing awareness and regulatory scrutiny, their production persists, mirroring the ongoing reliance on plastics in advanced manufacturing sectors. Even in the most remote regions, such as Antarctica and the Tibetan Plateau, PFAS have been found contaminating rainwater, demonstrating the inescapable reach of industrial pollution (Phys.org, 2022).

The Plastic Legacy: A Chemical Transformation

Plastics and synthetic chemicals are among the most persistent materials humans have ever created. On Earth, they fill our cities, roads, and oceans, forming the backbone of our infrastructure. Yet these very materials, in geological time, are fleeting. Exposed to the elements, plastics break down into microplastics, then further into molecules and chemical residues that mix into the dust of the world. Over the course of one to two billion years, all visible traces of plastic infrastructure would be erased, leaving only its molecular fingerprint behind.

On Earth, perchlorates are largely associated with industrial processes, forming as by-products in the production of plastics, explosives, and other synthetic chemicals. However, perchlorates can also form through the degradation of plastics under ultraviolet radiation, meaning that all of the unsustainable materials we produce today will eventually decompose into toxic compounds, making the planet’s surface increasingly hostile to life. In this sense, our plastic pollution today is not just an environmental issue—it is the long-term poisoning of our world.

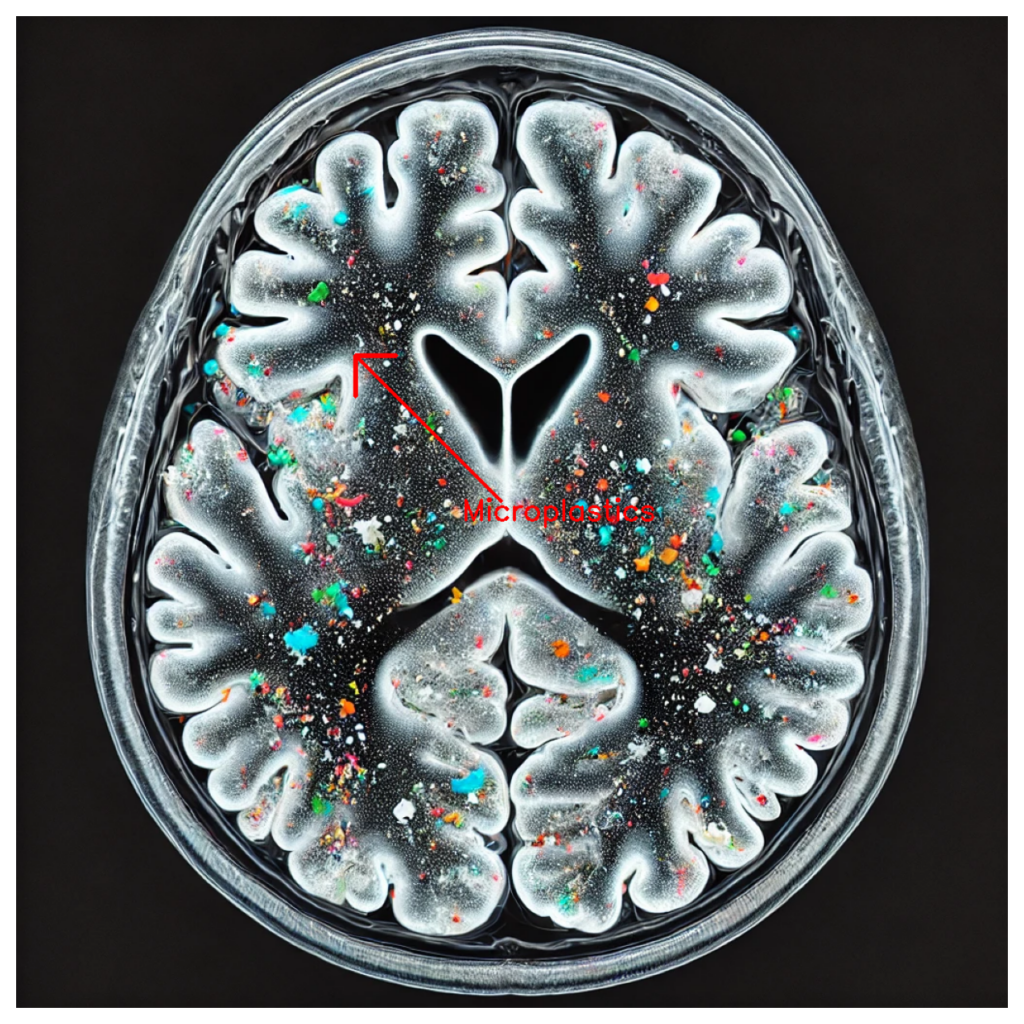

Recent studies have revealed alarming levels of microplastics in human tissues. For instance, research indicates that human brains may contain up to 7 grams of microplastics, particularly particles smaller than 200 nanometres, which can cross the blood-brain barrier. These particles are mainly composed of polyethylene and collect in brain blood vessels and immune cells. Switching to filtered tap water can significantly decrease microplastic intake—by almost 90%, from 90,000 to 4,000 particles a year (The Times, 2024).

A harrowing recent study found that most human brains now contain a spoonful of dementia-linked plastics, microplastics that have infiltrated the human bloodstream and lodged in brain tissue (MSN, 2024).

Fig. 1. A spoonful of microplastics, on average, exists in every human brain.

Moreover, microplastics have been detected in nearly 90% of protein food samples across 16 types, including seafood, pork, beef, chicken, tofu, and plant-based meat alternatives. The study found no statistical difference in microplastics concentrations between land- and ocean-sourced proteins (Food Safety, 2024). This pervasive contamination underscores the extent to which plastic pollution has infiltrated our food chain, raising concerns about the cumulative health effects of chronic microplastic ingestion.

The omnipresence of microplastics in our environment and bodies is a testament to the enduring legacy of plastic pollution. As these materials continue to accumulate, understanding their long-term impacts on human health and the planet becomes increasingly critical.

The Cost of Change vs. The Cost of War

If shifting global production to a sustainable model seems impossible, consider this: over $8 trillion has been spent on wars since 2000 (Costs of War Project, Brown University, 2023). Humanity has demonstrated an extraordinary capacity to fund destruction while dismissing the cost of sustaining life on Earth. If countries allocated just 3-4% of their GDP—the same level they commit to military spending—the transition to a sustainable global economy could be fully funded within decades. A $50 trillion investment over 30 years (IEA, 2021) would not only stabilise the climate but create a world that benefits humanity for thousands of years into the future. This is not just an economic decision—it is an investment in civilisation itself. Otherwise, our options on planet Earth will be evaporate well before the oceans do.

Bibliography

- American Chemistry Council (2023). Chemistry and Automobiles 2024.

- Lenton, T. M., et al. (2019). “Climate tipping points—too risky to bet against.” Nature, 575(7784), 592-595.

- Armstrong McKay, D. I., et al. (2022). “Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points.” Science, 377(6611), 1234-1243.

- International Energy Agency (2021). World Energy Outlook 2021.

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (2023). SIPRI Yearbook 2023.

- Costs of War Project, Brown University (2023). The Costs of War Since 2000.

- MSN (2024). “Most human brains now contain a spoonful of dementia-linked plastics.” MSN News.

- CHEM Trust (2024). PFAS Found in Remote Penguins.

- Phys.org (2022). PFAS in Antarctic Rainwater.